I have exceptional vision. According to my optician, it’s rated 20/5 and is so rare he’s only seen three cases of it in eight years of practice. It means I can see detail at twenty yards most people can see at five. It is an unproductive characteristic I did nothing to earn, but it is a very simple illustration of the importance of our subjective experience. I will quite literally see the world differently to most other people. Looking out of my office now beyond the veranda, bushes, banana trees, weathered bench, towards the banyan tree at the heart of our garden in Mauritius, I can pick out the texture of the bark on the vertical roots and the colour and intensity of the shadows between them. I don’t know what it’s like to see things any other way

A traditional craft: Writing by hand in Mauritius

We can’t perceive each other’s experiences of the world, but we can share those experiences through art. I’m of mixed heritage in every possible sense. A DNA test tells me I have significant Scottish, Welsh, Irish, Somalian, Sudanese, Italian, Spanish and Syrian ancestry. On paper, my mother was from England, my father from Egypt. My father’s family were dispossessed by the Egyptian revolution of 1952, and my mother’s family was a complicated one with much unhappiness, so she left home at a young age. My parents didn’t have much, but they had each other – so the saying goes. But in a world of bills, sometimes each other wasn’t enough and the stress of poverty and want drove most of the unhappiness I experienced as a child.

Justice and equality are at the heart of my work. Despite having been personally disadvantaged by revolution, I understand the ethos behind it. How is it fair that people who have acquired wealth through generations or who profit from the labour of others have so much when others who struggle and toil in socially valuable professions don’t have enough to feed their families? Why should a nurse have to switch off her heating and live in a cold apartment while an investment fund manager can afford to heat his or her seven-bedroom mansion and holiday homes? Why does the disgraced politician get a multi-million pound mansion and a comfortable retirement on the speaking circuit, while the junior doctor struggles to save for a house?

Allocation of resources is at the heart of so much social and political strife, and it is about to become an extremely relevant topic in the age of automation. When most work is done by robots or artificial intelligence, why should one person live by the beach while another struggles in the ghetto? How do we decide who gets what?

I propose a mechanism in the novel I’m currently writing, The Last Icon, which imagines a future sixty years from now. It’s a wild mechanism, but one that isn’t too far removed from the world we’re in now – more on that later.

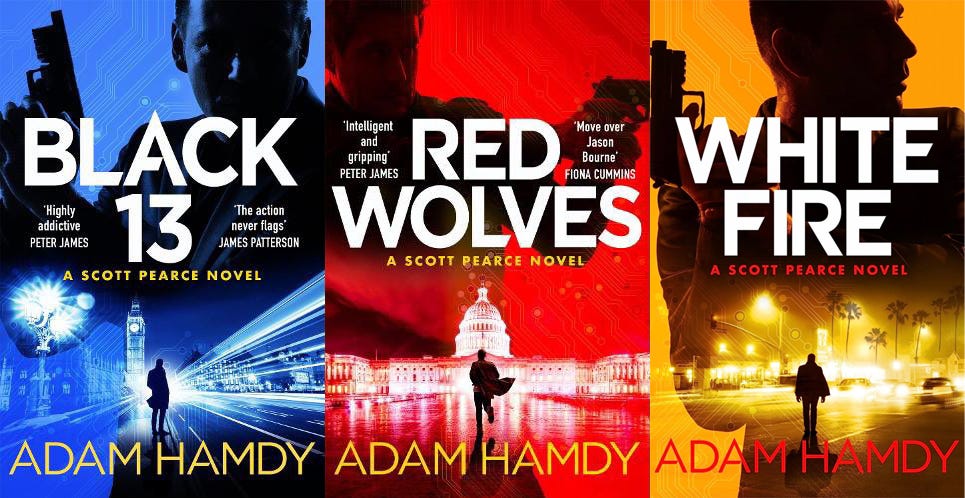

I believe in equality of all humans, which is why my books feature strong female and male characters and people of all cultural and social backgrounds. My 2020 novel Black 13 is set against a backdrop of a rise in far-right ideology. Those who seek to divide through hate are never far away, lurking in the shadows, but in times of hardship their message breaks through into the mainstream as people look for reasons to explain their poverty or struggle.

Prior to becoming an author, I was a strategy consultant and worked at board level at some of the biggest companies in the world. I’ve seen executives wipe out hundreds or thousands of jobs to protect the business’s bottom line. Your job was not taken by the refugee family, it was taken by the wealthy businessperson whose bonus is linked to profit performance, whose share options are worth more when the stock price rises.

Anyone who has studied the history of the corporation knows they were originally formed as collectives to pool assets and risk. They only acquired their own legal personalities later, and now they are at the forefront of everything we do. They have their own ethical and social values as well as legal identities, and where once the corporation might have acted to limit the losses of a syndicate backing an oceangoing cargo of tea, the corporation can now act as an insulating shield, absolving an individual of responsibility for harmful decisions. Dumping sewage in rivers? It was a corporate decision. Lowering safety standards to save money? Corporate. Suppressing the known harmful effects of a pesticide? It would impact profits.

The economy is the lodestar by which most governments and much of society steers, but ultimately the corporation dehumanises the world. It creates a distancing and shielding legal fiction, giving an entity that exists nowhere other than on paper more power and sometimes more rights than most people, and it’s a trend that’s accelerated with new technology.

In my 2016 novel Pendulum, I explore the impact of the internet on different people’s lives and ask how we’ve seen such radical transformation of the way we live without anyone stopping to ask whether we really need the technology we’re being peddled. We need to ask this question of artificial intelligence loudly and ensure that it serves the needs of the many and not the few.

Because that has been the fundamental problem throughout history. The world has typically been governed in the interests of the few, usually old men lacking in empathy. Historically the few have been those most willing to inflict violence, to conquer and dispossess. In modern times, power and control are now more commonly exerted through economic, political and social structures designed and run by the few. ‘Greed is good’ underpins the ultra capitalism that is at the heart of the modern economy, and this is a fascinating article on the psychological separation that ultimately results from such motivation.

The Rolls Royce Boat Tail is a luxury car that cost $28 million. A Porsche 911 costs around $150,000, a difference of $27.85 million. The average Mauritian annual income is $8,000, so if the person who bought the Rolls Royce had instead decided a Porsche was sufficient luxury, they could have supported almost 3,500 people at an average income for a year. The economy is a complex beast, and the purchase of that car created a few high-end jobs, and some of that money might eventually trickle down, but the point is that someone opted to spend $27.85 million to go a few milliseconds faster, to have a couple of decibels less ambient noise, to ride in slightly softer leather. Those marginal gains in luxury could have transformed the lives of thousands of people who struggle with the basics. This is a theme I explore in my forthcoming novel Deadbeat, and it’s a theme that is going to become central in a society that makes extensive use of artificial intelligence.

I’m not sure this is a good bio because I haven’t listed any accomplishments, but it gives you an insight into my thinking which will hopefully inform your decision to try one of my books.

Private Moscow with James Patterson (2020)

Private Rogue with James Patterson (2021)

The Other Side of Night (2022)

Private Beijing with James Patterson (2022)

Private Rome with James Patterson (2023)

Deadbeat (2024)